Sustainability: The Word is the Deed

November 26, 2019

Leading in the Era of Decarbonization

December 3, 2019

Sustainability: The Word is the Deed

November 26, 2019

Leading in the Era of Decarbonization

December 3, 2019A significant investment is needed to transform or replace today’s energy infrastructure. Whether goals are set to achieve local, national and even international decarbonization goals or to electrify the remaining population lacking regular access to electricity, energy in the modern age is an issue of finance and economy. The future of energy raises questions about what makes a good infrastructure investment, what capital exists to fund projects and how the public and private sectors should work together.

Capital is available, but most infrastructure projects today are not structured in a way that provides certainty of cash flows for investors.

New economic and business models have received lots of attention as the need to invest in new energy technologies has grown. While venture capitalists dove headlong into the clean-tech markets, their enthusiasm was short-lived. Many financiers are now motivated to hold their capital until futureproofed technologies come along; they want investments that ensure they won’t be stuck with useless or obsolete assets.

Analysts recognize that capital is available today for major clean energy projects. In fact, some argue that there is a surplus of capital. However, many projects fail to meet the necessary criteria for investors – whether they fall short of the minimum acceptable rate of return or other uncertainties outpace investors’ risk tolerance. The variety of hurdles facing innovative solutions that haven’t been proven yet impede change.

Performance Drives

Investment Decisions

Performance informs decisions in many aspects of the energy conversation – from how well a technology functions to how a financial decision performs for investors. A long-term, sustained financial commitment is necessary to achieve true infrastructure transformation and decarbonization goals. However, investments in the megaprojects necessary to achieve this vision need to perform for investors, which they generally have not yet been able to do.

As policymakers and communities look ahead to the projects they need, it’s important that investors are part of the conversation to discuss financial performance and how to best get these projects funded.

Power markets today are structured in a way that increases the uncertainty in cash flows.

As a result, there are often high interest and hurdle rates, which increase the cost of capital. This is why, in part, the projects being built today are largely utility-scale wind and solar with locked-in power purchase agreements that guarantee cash flow.

Committed financiers are not willing to simply wait for innovation to produce sure bets. They insist conversations need to be happening at all levels to incentivize every person to find a solution for decarbonization. In this view, education is the most important tool.

Outside of the industrialized world, financing issues are magnified in developing countries with significant infrastructure needs. Emerging economies face challenges with creditworthiness. Two common solutions have emerged in these situations:

There is a lot of progress being made in providing the type of financing for what’s necessary for decarbonization globally, but it’s still a long way behind.”

Action on decarbonization requires management and shareholder will combined with the ability to uphold fiduciary responsibilities.

Questions about the will to decarbonize often focus on public sentiment, but that’s only one part of the equation. Investors and shareholders also need to see the value of low-carbon power. Broadly, there is a growing interest in how to motivate corporations’ management teams and shareholders while allowing businesses to uphold their fiduciary responsibilities at the same time. Corporate finance and transparency rules, social impact standards and constraint risk valuations encourage greater attention to forms of sustainability.

One mechanism used to mitigate credible supply risk to long-term business operations is to require companies to disclose environmental, social and governance (ESG) performance if the information would be of interest to investors. However, developing these disclosures may be costly and the data may be unavailable in some cases.

Other instruments for investment are green bonds, which are mostly focused on energy, land-use and infrastructure investments. In total, broader, more consistent global policies will be required to develop independent and uniform standards. There must also be ways to monitor actual environmental compliance and outcomes.

There is an increasing and growing pool of capital that is saying we want the financial returns, but we also want the investor, on our behalf, to deliver an impact ‒ a social impact, an environmental impact.”

The urgency of decarbonization impacts investors’ time horizons just as time horizons influence investors’ attitudes about clean energy.

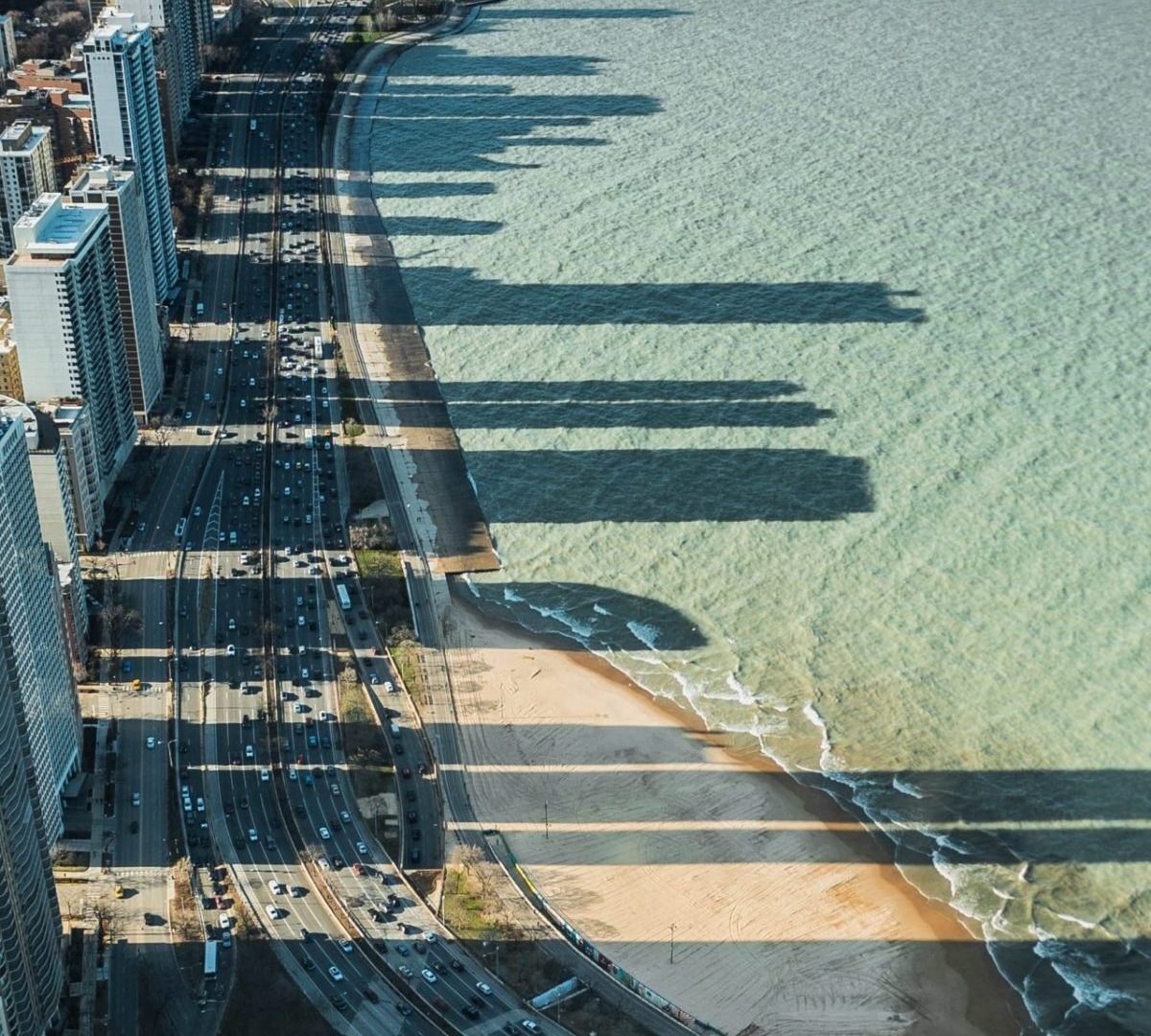

Investors with longer horizons generally see a greater need for decarbonization. They anticipate the incurred costs of pending environmental effects, such as increased flooding or extreme weather, on their assets. Investors with real estate assets may face obstacles securing flood or other forms of mortgage insurance. This devalues the asset that should have otherwise provided a long-term, reliable return. Over time, risks like this may translate into shareholder pressure on the boards of publicly traded companies to act on decarbonization.

The symposium’s consensus on the approach to decarbonization is that transportation and industry need to be electrified as much as possible.

Carbon-free generation technologies must produce the electricity to power those systems. The test lies in the significant investment required. There needs to be a conversation about how quickly even regulated, long-term investment structures, like rate-based infrastructure, can work with utilities to put that capital to work on decarbonization projects.

The public and private sectors must work together to achieve real infrastructure transformation.

Real infrastructure transformation is only possible with a cooperative effort between the public and private sectors domestically and internationally. In some cases, this may involve government stepping back to allow the private sector to innovate and, in other cases, the government may need to create incentives through taxes, subsidies or other mechanisms.

Further, government test beds and facilities, such as those available at Idaho National Laboratory, help companies demonstrate their technologies. These demonstrations help to de-risk investments before corporations put their capital to work on early-stage technologies. Such cooperative efforts need to continue.

Internationally, the public and private sectors need to find more creative ways to work together to rebuild and then preserve U.S. competitiveness.

In developing countries, nation-states and state-owned enterprises are stepping in to help build, operate and maintain foreign infrastructure projects, like nuclear power plants, while also financing them. This gives the financing nation-state a long-term role and influence in the developing country. A consortium of private-sector companies does not have the same influence and negotiating power as a government, leaving U.S. businesses and industries at a disadvantage. U.S. companies and the government need to work together to find ways to better compete on the world stage in this environment.

Western, industrialized countries are significantly underestimating the benefits of climate-smart planning and investment. According to the Global Commission on the Economy and Climate, bold action could deliver at least US$26 trillion in economic benefits through 2030, compared with business as usual.

The United States needs to get a lot more creative about how it thinks about the federal government interfacing and interacting with private industry.”